New Study Shows Increase in Hospital Use Following Medicaid Expansion Is Mostly Temporary

By Dee Mahan,

10.22.2014

A new study released by the UCLA Center for Health Care Research pokes holes in an argument that opponents of Medicaid expansion often use to justify their opposition: that giving uninsured people Medicaid coverage will lead to long-term runaway health care costs. Researchers at UCLA examined data from California’s early Medicaid expansion and found that this wasn’t the case.

According to the study, when low-income people gain access to health coverage for the first time, there is “pent-up demand” for hospital and emergency room care. Given the significant level of unmet need among new enrollees, this surge in demand for services is to be expected. But these higher rates of emergency room use and hospital care decline quickly. And within a year, those rates stabilize and resemble the rates of those who already had coverage.

One of the study’s co-authors and director of the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, Gerald Kominski, told NPR:

“What our findings say to the country is, concerns about Medicaid expansion being financially unsustainable into the future are unfounded.”

California’s early expansion program provides data that offer valuable insights into utilization of health services after a state expands Medicaid

UCLA researchers looked at data for Californians enrolled in free or low-cost health care programs the state ran from 2007 through 2013. Their results showed that, for individuals with the highest pent-up demand, emergency room and hospitalization rates were initially high but quickly declined and stabilized. After one year, this group’s hospital and ER use had returned to normal levels, and use of outpatient care was also stable.

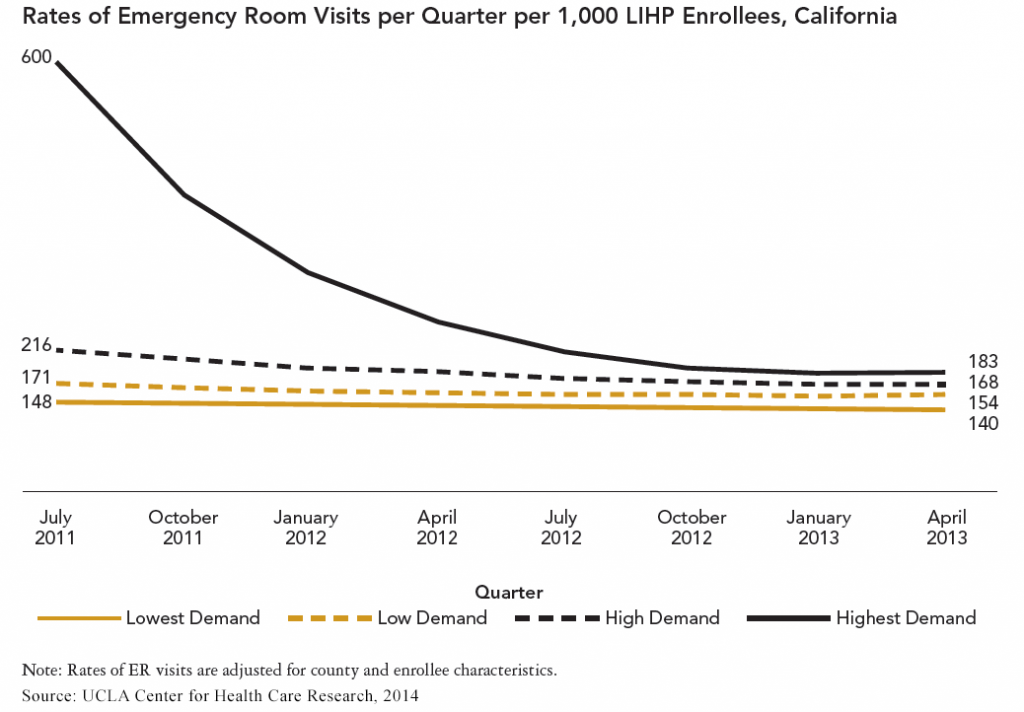

As the graph above illustrates, ER visits for people who previously had had the least medical care declined from a high of 600 visits per 1,000 enrollees in the first quarter of the program to a low of 183 per 1,000 at the end of the second year.

Between 2011 and 2013, the overall decline was 69.5 percent (183 ER visits). The report also shows that their hospital admissions declined sharply, from 194 to 42, a decline of 78.5 percent. (During the course of one of the health care programs, counties also initiated care coordination programs that may have helped normalize use more quickly.)

Researchers limited their study to adults who would be eligible for Medicaid expansion

From 2007 to December 2013—before expanding Medicaid last January—California ran two consecutive programs covering uninsured adults with incomes under 200 percent of the federal poverty level: the Health Care Coverage Initiative (HCCI) and the Low-Income Health Plan (LIHP). In 2014, enrollees were moved into Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program, or into the state-operated health insurance marketplace.

For the study, UCLA researchers looked at two years of LIHP claims data for more than 180,000 enrollees. They limited the sample to enrollees who met the income eligibility limit for the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion (133 percent of poverty).

Researchers grouped enrollees into one of four categories based on expected pent-up demand for care. This ranged from enrollees who used no services before having health coverage to those who had health coverage and used services. This design allowed researchers to compare the service use of those who had little to no access to medical care against those who had been in a health insurance program.

Results undermine argument against Medicaid expansion

This study is important because it debunks the idea that giving people Medicaid will permanently overwhelm the health care system. What can the 23 states that are still leaving federal Medicaid dollars on the table learn from California’s experience? Expand Medicaid now, when the federal government is paying 100 percent of the costs, so that demand is normalized when the state needs to cover a small percent of program costs.