Blueprint for Health Care Advocacy: How Community Health Workers Are Driving Health Equity and Value in New Mexico

11.12.2017

Across the health care system, there is tremendous interest and momentum in reforming the way health care is delivered and paid for in order to improve health care quality and outcomes and at the same time, reduce costs. These reform efforts create an enormous opportunity to improve resources, infrastructure, and incentives for interventions to meaningfully reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. Yet, if these reforms are not designed and implemented carefully, they could actually end up making these disparities worse.

Fortunately, there are some interventions that we know will improve health, reduce costs, and address disparities. Advocates can work to ensure that payment and delivery reform supports and expands these interventions, so that both health care value and health equity are improved. One example is the integration of community health workers (CHWs) into the health care system.1

Despite evidence that CHWs have a positive effect on access to care and health outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged communities, the lack of sustainable funding for their work prevents broader integration of CHWs into the health system. Advocates, CHWs, and other stakeholders in New Mexico have worked with Medicaid managed care organizations to address this challenge, and their experiences developing and implementing this model offer lessons for how other states can better fund and support CHWs.

CHWs are trusted members of their communities who, because of their unique skills and community relationships, are able to connect people with the health care system, provide education, and offer a broad spectrum of support to improve the health of individuals and their communities as a whole.

There is a great deal of evidence demonstrating the positive effect that CHWs can have on access to care and health outcomes. These effects include: greater use of preventive care, such as cancer screenings and vaccinations; improved management of chronic diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease; and greater numbers of patients connected to primary care. At the same time, by helping people avoid costly emergency department visits and hospital stays, CHWs can play a big role in reducing the overall cost of health care.2

Despite these proven benefits, CHWs remain undervalued and underutilized in the health care system. One major reason for this is the lack of sustainable funding for their work. Historically, most of the funding for CHW programs comes from charitable grants or from health care providers’ general operating or “community benefit” budgets. These kinds of funding streams are unpredictable, however, and are often time-limited or narrowly focused on a specific population or health condition. As a result, they are generally insufficient to support the full breadth of services and supports that CHWs can provide.

Medicaid Managed Care: One Pathway for Sustainable CHW Funding

Though many patients and communities could benefit from the support of CHWs, people enrolled in Medicaid would especially benefit from their services. This is because people on Medicaid are more likely to face adverse social determinants of health that CHWs are uniquely suited to address, such as living in unsafe housing, lacking access to nutritious foods, or facing language or cultural barriers to accessing care. As members of the communities they serve, CHWs understand these barriers and can serve as a bridge, connecting people to health care and social and community-based services.

Leveraging contracts with Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) is an attractive approach to funding CHWs within Medicaid, as over 75 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries nationwide are covered by managed care.3 Medicaid MCOs also generally have more flexibility to cover services like CHWs, even if they are not covered under traditional Medicaid state plan benefits. Furthermore, many states already require Medicaid MCOs to meet certain care coordination requirements, which CHWs can be effective in meeting.

This case study will describe how CHWs in New Mexico are being more sustainably funded with innovative financing through Medicaid MCOs, and will outline how CHWs and other advocates can work to implement similar Medicaid funding of CHWs in their state.

CHWs Can Improve Health and Reduce Costs for High-Cost, High-Need Patients

In New Mexico, contracts with Medicaid MCOs have been leveraged for many years to support the integration and sustainable funding of CHWs. One model, now known as Integrated Primary and Community Support (I-PaCS), began as a pilot program in 2005, using CHWs to provide Intensive Patient Support (IPS) to patients with complex health and social needs. Though such individuals represent only about 5 percent of the patient population, they generate about 50 percent of all health care costs, due to their frequent use of emergency department (ED) and other health care services.4 This pilot was implemented by Molina Healthcare of New Mexico (MHNM), a Medicaid MCO that worked with partners at three sites: a University of New Mexico (UNM) clinic in Albuquerque, a clinic in Las Cruces with UNM staff, and Hidalgo Medical Services, a federally qualified health center in Silver City.5

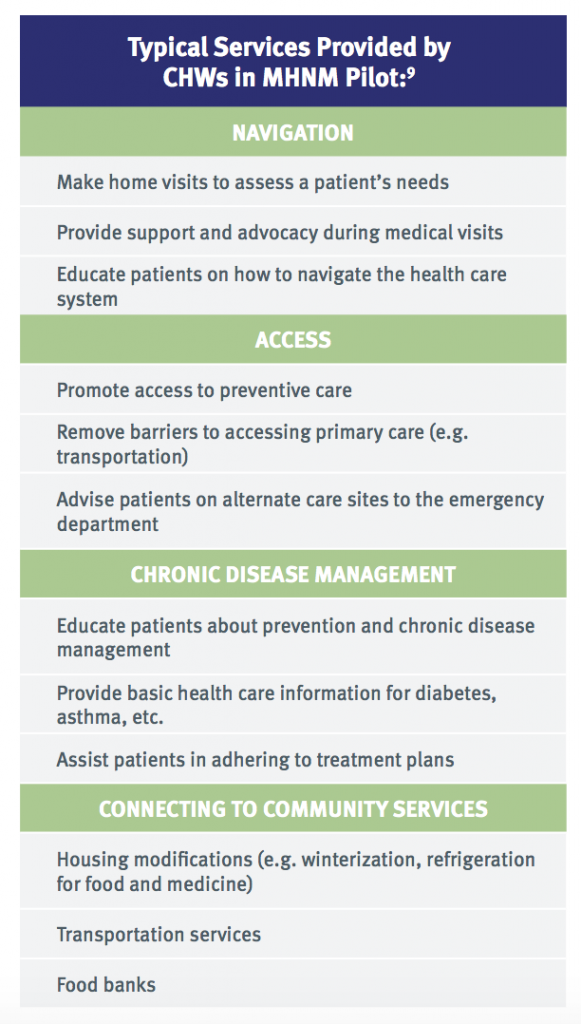

Financial support for the CHWs and the services they provided came from an additional per-member-per-month (PMPM) payment that MHNM paid to the clinics for each MHNM patient with complex health and social needs that received CHW services. For each of these individuals, MHNM paid the clinics an additional $256 PMPM in 2005, which was increased to $306 in 2007 and later to $321 in 2009. This funding supported CHWs in providing a wide range of services and supports, including helping patients better access and navigate the health care and social service systems, manage their chronic diseases, and obtain necessary resources, such as refrigerators.6 Each CHW was responsible for 25-30 patients, with a typical “length of stay” in the program of 3-6 months. Under this arrangement, patients continued to receive services for 3-6 months, until they felt they had the resources and education necessary to better use and access the appropriate health care services and were able to follow through with their treatment plans.7 Importantly, CHWs collaborated with other members of the care team, the patient, and their family to develop an individualized care plan based on the patient’s goals.8

Interdisciplinary team-based care management is an important tool to enhance the impact of CHWs. At one of the pilot sites, Hidalgo Medical Services, a team-based care delivery system also helped ensure that CHWs were being utilized effectively. Instead of being used for general clinical support, money from the additional PMPM that Hidalgo received from MHNM for this pilot supported a “Family Support Services” department. This department was co-equal with the clinic’s other departments, elevating the CHWs and their particular skills and expertise within the care team. Combined with the “automatic referral” of these patients to the Family Support Services department, this design ensured that CHWs were a valued and integrated partner on the care team and established a dedicated revenue stream for CHWs that de-linked payment from the medical office visit.10

After six months of receiving this intensive support from CHWs, patients across the three different sites had fewer visits to the ED, fewer inpatient admissions, and used fewer prescriptions. As a result, the program saved $4 for every $1 invested in it. Responses from patients who received services from this pilot also indicated its success, as patients were glad to have help in completing important preventive screenings, including for blood glucose and cholesterol levels, and for breast and cervical cancer.11 Because of this success, MHNM expanded this model to other clinics, and the other three Medicaid MCOs in New Mexico decided to contract with clinics to implement similar programs. This program has now been expanded to sites in all 33 counties in New Mexico, and aspects of the model were replicated in 10 other states served by Molina Health Plan MCOs.12

Using CHWs to Support All Patients and Improve Community Health

Building on the success of the model described above, UNM, Hidalgo Medical Services, and MHNM came together to test an expansion of the pilot program to help lower-risk patients and improve community health and prevention with CHWs. To support this expanded model, MHNM paid a smaller PMPM (between $6 and $11) for each non-complex MHNM patient receiving services from the clinics to support two additional components of I-PaCS: Comprehensive Patient Support (ComPS) and Community Health Improvement Strategy (CHIS).13

Patients who are identified as facing adverse social determinants of health, but who don’t need quite the level of support provided to the highest-cost, highest-need patients, receive support under ComPS. At this level of the program, CHWs still provide a range of services to patients, including providing them with information about social and community-based resources, helping them sign up for public benefits such as Medicaid or food assistance, and providing them with one-on-one health education and support. CHWs also play a key role in ensuring these patients are up-to-date on important preventive screenings, such as cancer screenings, wellness exams, eye and dental exams, and immunizations.14

The third component of I-PaCS, the CHIS, is closely informed by the other services provided under I-PaCS. All patients under I-PaCS are screened for adverse social determinants of health, and the responses to these screenings in the aggregate help clinics identify and prioritize the community’s needs that will be addressed by CHIS. CHWs then reach out to community-based organizations and other community leaders to share their findings on the community’s health needs, identify existing resources, and develop a comprehensive plan to address any gaps. For example, CHWs might work to improve access in the community to nutritious food, exercise facilities, or better paying jobs. The CHIS program uses the CHWs’ unique knowledge of the community and their relationships with key community members to drive improvements in economic and social services that will improve the health of the community’s entire Medicaid population.15

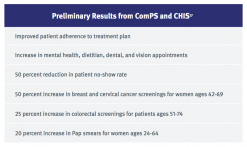

Though evaluation of the ComPS and CHIS is still in its preliminary stages, early results are promising and indicate patients are better connected to care and have greater uptake of preventive services. There is also improved satisfaction among providers who are working with CHWs.16

Using Medicaid Managed Care to Sustainably Fund CHWs in Your State

State Requirements for Medicaid MCOs

When states contract with health insurers to serve Medicaid beneficiaries, the state has significant flexibility in determining the types of care delivery requirements that MCOs must meet. To implement managed care in a state’s Medicaid program, the state must first develop a Medicaid waiver or state plan amendment application that it will submit for approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Prior to submitting these applications or renewals, states are required to seek input from stakeholders and make the proposed waiver available for public comment.18 This public comment requirement presents an important opportunity for advocates to encourage their state to include CHW requirements in the waiver application they submit to CMS, and subsequently in its contracts with Medicaid MCOs.

Though the original pilot program described above predates New Mexico’s 2012 application to CMS to renew its Medicaid managed care program, the requirements the state has put in place for managed care have helped contribute to the continued expansion of that and other CHW models. In its 2012 waiver application, New Mexico included the following in a section discussing health literacy (emphasis added):

Under the Section 1115 demonstration program, New Mexico will require plans to conduct aggressive outreach to their recipients and offer information both about how to navigate and most efficiently use the health care system as well as how to manage their health conditions. Much of this work can be most effectively done through the use of a trained, “lay” workforce to work with recipients to engage in their own health. Whether the plans “make or buy” this service, it will be a contractual requirement that community health workers be available as a resource to both the care coordination staff and to recipients who seek to educate themselves about their health. In addition, plans will be expected to develop culturally sensitive, relevant and accessible materials focused on using the health care system wisely and effectively and addressing chronic health care issues.19

In the subsequent Request for Proposals that New Mexico released inviting bids from health plans to serve as a Medicaid MCO, the state required interested plans to detail how they would:

- Build and maintain “a network of Community Health Workers (community health advisors, lay health advocates, promotoras, outreach educators, community health representatives, peer health promoters, and peer health educators).”20

Contracts with Medicaid MCOs further specify the CHW requirement. In its contracts with Medicaid MCOs, New Mexico:

- Makes it clear that when calculating the maximum caseloads that each care coordinator can have, CHWs can serve as a care coordinator and be included in determining whether or not the MCO is meeting the required ratios of care coordinators to Medicaid beneficiaries;

- Requires the MCO to “encourage the use of Community Health Workers in the engagement of Members in care coordination activities;”

- Requires the MCO’s Health Education Plan to indicate how they will work with CHWs to improve beneficiaries’ health literacy. Specifically, plans have to make CHWs available to their enrollees to:

- “Offer interpretation and translation services;*

- Provide culturally appropriate Health Education and information;

- Assist Members in navigating the managed care system;

- Assist in obtaining information about and access to available community resources;

- Provide informal counseling and guidance on health behaviors; and

- Assist the Member and care coordinator in ensuring the Member receives all Medically Necessary Covered Services.”

- Requires that the plan “ensure that Community Health Workers receive training on Centennial Care [New Mexico’s Medicaid program], including the integration of physical and Behavioral Health as well as long-term services;” and

- Requires the plan’s annual Health Education Plan to “have a separate section describing Health Literacy efforts including the use of Community Health Workers.”21

As New Mexico seeks public input for its 2018 waiver renewal, the state reports that Medicaid MCOs are currently employing over 100 CHWs, either directly or by contracting with another organization.22 However, not all of the CHWs employed by these Medicaid MCOs are working in a health center or other community-based setting as described above. Rather, many are hired directly by the Medicaid MCOs and connect with patients mostly over the phone.23 Although telephonic care management interventions are widespread in Medicaid, it isn’t appropriate to describe a purely telephonic program as a true CHW intervention: this type of model is not aligned with the community “rootedness” and in-person connections that define CHWs and make them so effective.

Contracting with Medicaid MCOs

Providers may be interested in contracting directly with the relevant Medicaid MCOs in their area to sustainably finance CHW positions. Program staff involved in implementing the I-PaCS model and its preceding pilot program have noted that this can be a challenging process, especially as leadership of the MCOs and staff involved in the contracting process frequently change. They suggest obtaining multi-year contracts, when possible, in order to have some continuity in how the program is implemented and financed.24

As producing cost savings is typically a central motivator for Medicaid MCOs, it is important to be able to demonstrate the return on investment (ROI) that the MCO can expect to gain from funding such a program. This can be achieved by carefully evaluating a smaller, existing pilot program at a health center, or from modeling the ROI that could be realized if an existing program were to be implemented in a particular community. For example, The Connecticut Health Foundation recently released a report that modeled the benefits and cost savings that could be realized if the IPS program described above, targeting the highest-need patients in New Mexico, were implemented in New London County, CT. They predicted that over three years, this would result in an 81 percent reduction in hospitalizations and a 69 percent reduction in emergency department visits for the patients in such a program, and that the financial ROI would be $2.40 for every $1 invested.25

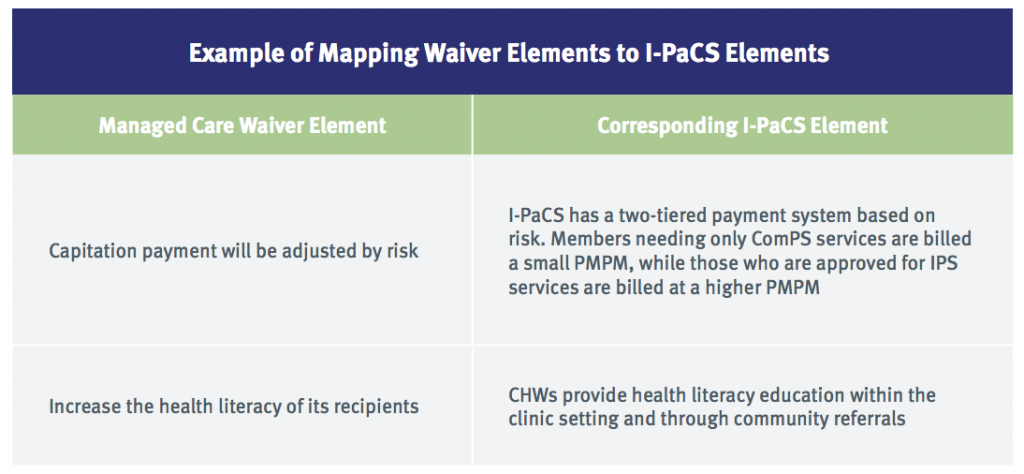

It may also be helpful to “map” any existing Medicaid managed care requirements to elements of a prospective program. For example (see table, above), the I-PaCS toolkit maps how certain elements of New Mexico’s managed care waiver match with elements of I-PaCS. This analysis shows Medicaid MCOs that the CHW program is not adding new requirements, but is instead helping them meet existing requirements.26

Considerations for Community Leaders and Stakeholders

Community leaders and stakeholders interested in implementing and adapting New Mexico’s CHW models in their communities should consider certain issues as they work with interested partners to plot a course forward.

What role do Medicaid MCOs play in your state?

The models described above relied on New Mexico’s use of managed care companies to deliver care to Medicaid beneficiaries. Though nationally over 75 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in managed care, not all states use managed care, and those states that do vary widely in which services and populations are covered through managed care.27 Understanding which services and Medicaid beneficiaries are covered through managed care in a particular state is essential for understanding how Medicaid MCOs can be leveraged to better integrate and sustainably fund CHWs. As stated above, a state’s federal filing for Medicaid managed care application or renewal provides an opportunity for advocates and community leaders to influence how Medicaid MCOs use and support CHWs.

What should you do about CHW certification?

There are currently efforts underway in many states to establish state-level certifications for CHWs via legislation. The goals of such legislation are often to standardize the training and core competencies of CHWs; to advance workforce development; to establish CHWs as a more recognizable occupation; and to improve the perception of accountability. To be sure, these are important objectives, and may help to better integrate CHWs into the health care system and convince more health care payers (Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial insurance carriers) to directly pay for CHW services. However, it is important to note that much of CHWs’ effectiveness is rooted in their deep connections with the communities they serve, and they may face some of the same financial, educational, language, geographic, cultural, and other barriers as the people they serve. Such barriers could put certifications out of reach for many.

In 2014, New Mexico enacted the Community Health Workers Act, which instructed the secretary of health to establish a voluntary CHW certification program. CHWs can become certified by completing state-endorsed training programs, or, for those who have been working as CHWs for a certain length of time, by being “grandparented” into certification.28 Voluntary certifications, like in New Mexico, are often thought to help avoid the barriers that a required certification program would create for people from marginalized communities. However, certifications that are technically voluntary could easily become required in practice, if Medicaid MCOs, other health plans, or health care providers, such as hospitals, begin requiring it for all or most CHW positions.

Importantly, the CHWs in I-PaCS are not required to be certified or to have completed a particular type of coursework or training. Instead, in the initial pilot, each of the clinics hired its own CHWs, who then all went through a training designed specifically for that program. As I-PaCS developed, it built its own training curriculum, though clinics implementing I-PaCS are still free to hire their own CHWs and there are still no certification requirements put in place by this particular model. Importantly, the Medicaid MCOs did not require certification or particular training programs, indicating that, at least in certain circumstances, payers are willing to pay for the services of CHWs who were trained at the discretion of their employers.

How do you ensure support for “upstream” prevention and community health?

CHWs can contribute significantly to improving the overall health of communities over the medium and long term by promoting prevention and improving health knowledge more generally. However, staff who were involved in implementing the parts of I-PaCS that are not targeted at the highest utilizers have noted that it is proving more difficult to keep Medicaid MCOs interested in funding these parts of the model. There are two reasons for this:

- Extended ROI timeframe: Programs working with people who aren’t the highest utilizers of health care services will not garner the same 4:1 ROI as the initial “downstream” New Mexico pilot did. By targeting patients with lower utilization and focusing on prevention and community health, it will take much longer for those cost savings to materialize, possibly well beyond the timeframe an MCO would view as a good ROI. Working with a very sick person who is using a lot of costly health care services today so that they use less of these expensive services six months from now is a compelling case for MCOs. But working with someone at risk for diabetes or other chronic condition to prevent them from having a heart attack or needing an amputation 10 years in the future could be a more difficult financial argument to make. By the time such an intervention can produce positive results, the patient might be covered through a different Medicaid MCO or another health plan. Still, despite the challenges of demonstrating ROI within a timeframe that would appeal to a Medicaid MCO, it is notable that United Healthcare’s New Mexico Medicaid MCO is still supporting the ComPS and CHIS components of the I-PaCS model at two clinics in New Mexico on an ongoing basis. Providers and community health leaders can also propose using clinical preventive services protocols, such as blood pressure checks and medication adherence, as proxy measures of health status improvements that may take longer to materialize otherwise. Tying these measures to quality incentives that already exist in Medicaid MCO contracts could be a useful advocacy strategy.

- Competition and brand differentiation. MCOs are competing with one another for beneficiaries, so it is important for them to distinguish the services they offer from those offered by other plans. This serves as a disincentive for the plans to offer a common program—in this case, I-PaCS. Each MCO will want to modify or vary their program to set their plan apart from competitors.One way to address this challenge is to encourage the state to add requirements to managed care contracts related to prevention, community health, and other services that Medicaid MCOs are not otherwise incentivized (for example, by the likelihood of ROI) to provide. Advocates should reach out to CHWs, community health centers, and community-based organizations to help identify what some of these key services and roles of CHWs might be.

Which institution employs the CHWs?

In order to ensure the effectiveness of CHW interventions, it is important that CHW programs and those hired to serve as CHWs stay rooted in a true community-based, community-empowering model. As CHWs become an increasingly popular concept among providers, insurers, and others who are newcomers to the CHW field, there is real concern that many of these stakeholders are simply “jumping on the bandwagon” without a true understanding of the work CHWs do and what makes them so effective. For example, a requirement that Medicaid MCOs have a certain ratio of CHWs to beneficiaries could lead to the Medicaid MCO hiring a cohort of people as CHWs who have little or no connection to the communities they are supposed to be serving, and who may not fully implement the community-based and home-visiting elements crucial in so many CHW programs.

In addition, the expansion of CHW programs that employ CHWs who live and work in underserved communities, or are employed by recognized community-based organizations or trusted community health centers located in these neighborhoods, has an added benefit: economic development. Bringing more jobs and resources to marginalized communities helps address some of the social determinants of health that may be disadvantaging them.

Advocates can help take advantage of this opportunity by ensuring that an MCO’s contracting requirements for CHWs better define who a CHW is and what services they provide. More specifically, they can advance requirements for Medicaid MCOs to hire CHWs by contracting with community health centers and community-based organizations who better know the communities being served, and who have a long history of working with CHWs.

How do you create space for CHWs to lead?

Finally, it is important that CHWs are substantially represented and play leadership roles in any efforts to increase funding for CHWs through Medicaid MCOs, or through any other mechanism. An official policy statement adopted by the American Public Health Association that called for any working groups or governing boards that deal with CHW workforce issues to be comprised of at least 50 percent CHWs is a good starting point to ensure that any CHW-related policies are clearly informed by CHWs themselves and the communities they serve.29

Community health workers have a proven track record of improving health outcomes for marginalized communities. Yet, sustainable funding remains the chief barrier to more widespread use of CHWs. In New Mexico, advocates, CHWs, and providers have partnered with Medicaid managed care organizations to develop innovative strategies to sustainably fund and better integrate CHWs into the health care system. By adapting this and other successful models, other states can better support CHWs in serving their own communities.

*Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act requires that limited English proficient individuals be provided with “qualified” medical interpreter services. To be “qualified,” these individuals must abide by interpreter ethics, speak English and another language fluently, and understand the necessary vocabulary needed in a medical setting (see http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/05/14/hhs-issues-health-equity-final-rule/). While the MCO contract requires that CHWs be made available to provide translation and interpretation services, not all CHWs are trained medical interpreters. Nevertheless, bilingual CHWs can be a very important resource for Limited English Proficient patients and families to use as they seek to access culturally competent and language-accessible care and other services.

Full endnotes can be found on download version of this product (PDF).